You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tied triplets counting in Stick Control

- Thread starter ctdrummer

- Start date

Numberless

Platinum Member

What do you mean by tied triplets? I'm looking at page 8 right now and the first exercise is 4 eight notes followed by six eight note triplets.

Count them as: 1 and 2 and 3 tri plet 4 tri plet.

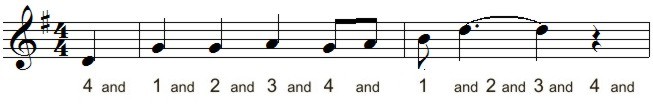

For future reference, a tie is a curved line that extends from one note to another, like this one:

If you need some help counting triplets, check this video lesson:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MksFn4Q4nAw

Count them as: 1 and 2 and 3 tri plet 4 tri plet.

For future reference, a tie is a curved line that extends from one note to another, like this one:

If you need some help counting triplets, check this video lesson:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MksFn4Q4nAw

Swiss Matthias

Platinum Member

I don't have Stick Control near me at the moment, but generally you can count through

tied notes as if there wasn't anything special, and just not play the tied note (the 2nd).

Generally in music a tied note would mean holding the note longer, but on drums it just

means waiting longer until the next stroke follows. Tied notes aren't really necessary for

rhythmical instruments, because we normally don't sustain notes on purpose.

tied notes as if there wasn't anything special, and just not play the tied note (the 2nd).

Generally in music a tied note would mean holding the note longer, but on drums it just

means waiting longer until the next stroke follows. Tied notes aren't really necessary for

rhythmical instruments, because we normally don't sustain notes on purpose.

toddbishop

Platinum Member

Those are two beats of regular 8th note triplets beamed together. Count and play the measure 1 & 2 & 3 trip-let 4 trip-let.

I don't have Stick Control near me at the moment, but generally you can count through

tied notes as if there wasn't anything special, and just not play the tied note (the 2nd).

Generally in music a tied note would mean holding the note longer, but on drums it just

means waiting longer until the next stroke follows. Tied notes aren't really necessary for

rhythmical instruments, because we normally don't sustain notes on purpose.

Yes and no, Swiss. On timpani, for example, the length of the note is often adjusted by muting. That's also a achievable on snare drums and tom toms using various techniques if you want to get precise. I've been known to mute the sustain of my snare and toms with my hands or sticks when I'm playing a note that needs to be cut off to leave silence along with the band. Alternatively, I'll use buzzes to lengthen notes. Honouring the length of the note is definitely possible with cymbals and with hihats (open/closed), etc. A bass drum can be muted/shortened or lengthened by burying the beater or allowing it to come out, depending on your tuning/muffling. Check out this guy using mute/open tones on his floor tom to mimic a surdo, for instance: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1uw7ZCC9L4

I also think it's really important from a musical standpoint for drummers to learn to hear the length of notes the same way a horn player or singer would so that we can accompany those parts well and in a commensurate style.

Take the case of four swung eighths ending with a tie to the following quarter compared to four eighths followed by a rest. There is a big difference between how I would play the first one: Do-vi-doo-AHH, and the second: Do-vi-do-DAT. Those aren't the same rhythm and in the first case I'd be far more likely to use a sostenuto sound like shoulder crash on a ride, or a crash cymbal to mimic the length that the horns are playing, whereas in the former case I'd be more likely to use a sharp, precise sound like a rimshot jab on the SD or a BD.

Moreover, I find that hearing the length of notes (ties and dots included) helps my time and feel. I was encouraged to sing the full length of note when learning to read and play, and I make my students do it, too. I think this helps connect us to a more lyrical and melodic conception of what we're playing. The same way singing subdivisions will fill the space between notes, giving the note it's whole length and breadth has the same effect.

Here's another example. A dotted-eighth-sixteenth rhythm (dots act like ties) has a different feeling and phrasing than a sixteenth followed by two sixteenth rests and a sixteenth note. Sing the two to yourself giving the notes their correct length and you'll hear the tendency to think of the second one in a more staccato fashion. There's also the tendency to weight both notes evenly, whereas in the dotted-eighth-sixteenth rhythm, even in the absence of accent markings, we'll still tend to put more weight into the first note. The difference in feel between playing both notes at equal dynamic and playing the long note with even just a smidgen more weight is massive. Record yourself playing a groove with each as the ostinato and see if you hear it. I think the conception we have in our heads makes its way into the sound we're making on the drums. As I mentioned earlier, trying playing the first rhythm using a buzz and a single stroke as an example of how we might play the length of the note as a melodic instrument would. Or use an open and closed Hihat to play both rhythms. They aren't alike in the slightest.

Also, without ties and dots, the page would be cluttered with a lot more devilish little rests, which are murder on the eyes.

Last edited:

Swiss Matthias

Platinum Member

Yes, agreed, if you wanna dig deep. I rather thought about everyday drumset playing. My

post isn't very accurate when it comes to more classical playing ie.

Again, speaking from a pop/rock/jazz drumset point of view .

.

post isn't very accurate when it comes to more classical playing ie.

Yes, and that's the main reason we have long notes and sometimes even tied notes.Also, without ties and dots, the page would be cluttered with a lot more devilish little rests, which are murder on the eyes.

Again, speaking from a pop/rock/jazz drumset point of view

Yes, agreed, if you wanna dig deep. I rather thought about everyday drumset playing. My

post isn't very accurate when it comes to more classical playing ie.

Well, I dunno. I know I tend to think this way in pop/rock and definitely in jazz as the 4 eighth note example illustrates.

Swiss Matthias

Platinum Member

Of course you can play quarter notes as rolls, and sixteenth notes as single strokes

on the snare, for example. But normally it's not the way it's meant to be.

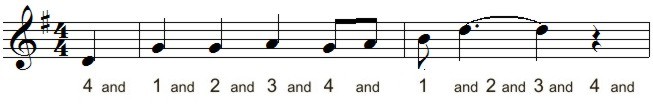

If you take this groove:

It's not the idea that you play the snare on 1+e short, but the snare on 4 as a long quarter note.

on the snare, for example. But normally it's not the way it's meant to be.

If you take this groove:

It's not the idea that you play the snare on 1+e short, but the snare on 4 as a long quarter note.

Attachments

Of course you can play quarter notes as rolls, and sixteenth notes as single strokes

on the snare, for example. But normally it's not the way it's meant to be.

If you take this groove:

It's not the idea that you play the snare on 1+e short, but the snare on 4 as a long quarter note.

I don't see a tie in this example.

toddbishop

Platinum Member

It's not the idea that you play the snare on 1+e short, but the snare on 4 as a long quarter note.

Written-out beats can be misleading that way- a true musical example would reflect the durations of the part the beat is meant to accompany.

Of course you can play quarter notes as rolls, and sixteenth notes as single strokes

on the snare, for example. But normally it's not the way it's meant to be.

If you take this groove:

It's not the idea that you play the snare on 1+e short, but the snare on 4 as a long quarter note.

It might, actually. In fact, if I was teaching that groove to a student or learning it myself, I would sing/have them sing the SD/BD as written, giving the proper length to the notes. If you do this, it quickly gives the groove a melodic quality. Also, thinking of that quarter on 4 as having some length will usually help a student who tends to rush 1 on their bass drum. Singing the whole length of the BD note on 1 tends to help us not rush the "a" of 1, too.

Alternatively, I would tend to think of the note on the "a" of 1 as extending to the BD 8th note on the "and" of 2 - assuming a tie. But that's a different story altogether

I don't see a tie in this example.

Dots act much like ties.

Dots act much like ties.

Thanks! I'm still learning this stuff.

ctdrummer

Member

Thanks everyone, and yes, sorry for the terminology mistake using the word "tie" incorrectly.

The video "Numberless" pointed to is helpful. My main question was how a eight note triplet is counted/played compared to the four eighth notes. Unless I have it wrong, there is nothing different about a triplet in this case. If there are 4 "beamed" eight notes followed by two sets of eight note triplets beamed together, is it really just 10 eighth notes? My mind says to play the triplets faster, but this is not correct.

Please forgive my confusion.

The video "Numberless" pointed to is helpful. My main question was how a eight note triplet is counted/played compared to the four eighth notes. Unless I have it wrong, there is nothing different about a triplet in this case. If there are 4 "beamed" eight notes followed by two sets of eight note triplets beamed together, is it really just 10 eighth notes? My mind says to play the triplets faster, but this is not correct.

Please forgive my confusion.

Thanks everyone, and yes, sorry for the terminology mistake using the word "tie" incorrectly.

The video "Numberless" pointed to is helpful. My main question was how a eight note triplet is counted/played compared to the four eighth notes. Unless I have it wrong, there is nothing different about a triplet in this case. If there are 4 "beamed" eight notes followed by two sets of eight note triplets beamed together, is it really just 10 eighth notes? My mind says to play the triplets faster, but this is not correct.

Please forgive my confusion.

It's fairly straightforward. In the case of eighth notes, we're dividing a quarter note into 2 even parts. Usually we count this as 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &. With eighth note triplets we divide a quarter note into three EVEN parts. Usually we count this as 1-trip-let 2-trip-let 3-trip-let 4-trip-let.

Try this exercise to help understand.

A.

1. Tap your feet at slow, even intervals.

2. Clap two notes per foot tap (eighth notes)

3. Count each clap: i.e. 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &

Get comfortable with that. Your feet are playing quarters and your claps are 8ths.

B.

1. Tap your feet as above.

2. Clap three evenly spaced notes per foot tap.

3. Count each clap: i.e. 1-trip-let 2-trip-let 3-trip-let 4-trip-let

Get comfortable with that. Your feet are playing 1/4s and your claps are 8th-note-triplets.

Once you can do each comfortably, trying doing them back-to-back moving from a bar of 8ths to a bar of 8th-triplets and back again. Make sure that the foot taps/quarter-notes stay steady from the first bar to the second. Count all claps as above.

Once you're comfortable with that. The Stick Control exercises in question can be counted 1 & 2 & 3-trip-let 4-trip-let. Tap your feet and clap the rhythm before even picking up sticks to play the sticking exercises.

Last edited:

motleyh

Senior Member

Thanks everyone, and yes, sorry for the terminology mistake using the word "tie" incorrectly.

The video "Numberless" pointed to is helpful. My main question was how a eight note triplet is counted/played compared to the four eighth notes. Unless I have it wrong, there is nothing different about a triplet in this case. If there are 4 "beamed" eight notes followed by two sets of eight note triplets beamed together, is it really just 10 eighth notes? My mind says to play the triplets faster, but this is not correct.

Please forgive my confusion.

Careful -- an eight-note triplet is not the same as a regular eighth note, even though it has the same kind of single flag or beam on it. Your mind is right - triplets are a little faster than eighth notes, in that you fit three of them within a beat rather than just two.

In the example on page 8, it looks like you're confused a little by the fact that the last two notes of triplets are beamed together, but it's six notes within the time of two beats -- or three notes within each of those two beats, which is the same thing. In the same way, the first four eighth notes are also beamed together: four notes during the time of two beats or two notes per beat. If it had been written with each note beamed by itself, it would probably be clearer.

So what you have there is: four notes that fit into the time of two beats, followed by six notes that fit into the time of two beats.

Swiss Matthias

Platinum Member

Sorry, that example was meant for the side discussion I have with Boomka. Sorry forchaymus said:I don't see a tie in this example.

hijacking the thread...

True, but this practically mixes up cause and consequence. First there was a soundingIt might, actually. In fact, if I was teaching that groove to a student or learning it myself, I would sing/have them sing the SD/BD as written, giving the proper length to the notes. If you do this, it quickly gives the groove a melodic quality.

groove pattern, the notes are an attempt to write that down. If you interpret the long notes

literally, you move away from the original idea. With that being said, I again am talking about

very pragmatical every day use of drum notation. In my example, notating the snare hit on 4

with a - say - 16th note and three sixteenths worth of rest would be more accurate, but,

in your words, that would make the measure cluttered with a lot more devilish little rests, which are murder on the eyes. That's what I'm trying to say. Drumset notation loses

accuracy for the sake of clarity and simplicity.

Sorry, that example was meant for the side discussion I have with Boomka. Sorry for

hijacking the thread...

True, but this practically mixes up cause and consequence. First there was a sounding

groove pattern, the notes are an attempt to write that down. If you interpret the long notes

literally, you move away from the original idea.

That's a matter of perspective. I could say that in certain circumstances, truncating the note in notation takes us further away from the original conception. When I conceive that groove I think of that note being long. How is that incorrect? And plenty of things are composed without being played first. Notation isn't just recording.

In my example, notating the snare hit on 4 with a - say - 16th note and three sixteenths worth of rest would be more accurate,

Again, this is a matter of perspective and musical conception, not fact. Also, even if we want to talk about sound alone - seperate from conception - if I play a SD with a long sustain the current version is more accurate. If I play a SD with loose snares, it's more accurate. But, back in the world of conception, as I said above, I think there are solid reasons for thinking of those notes as having length - i.e more accurate time playing, a greater sense of melody and space, etc. Also, as Todd Bishop pointed out, having those notes relate to how other instruments in the ensemble are playing THEIR notes is important. As I mentioned above, there is a massive difference between conceiving of a dotted-8th-16th rhythm and the first and last 16ths of a group of 4. If the rest of the ensemble is playing/reading dotted-8th-16ths, that should be reflected in the drum part.

in your words, that would make the measure cluttered with a lot more devilish little rests, which are murder on the eyes. That's what I'm trying to say. Drumset notation loses

accuracy for the sake of clarity and simplicity.

Drum notation loses accuracy when it doesn't accurately convey the musical conception of the composer. If I conceive of long notes, there should be long notes. If I conceive of short ones, there should be short ones. Musical notation is as much about expressing conception as trying to record sounds.

Anyway, I'm finished with this. We're not going to agree and we're about to start going in circles.

Last edited: